Personal or Shared, Analog or Electric—Bike Your Way in Boston

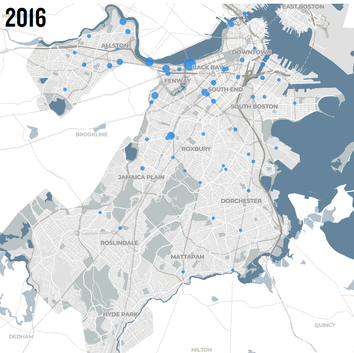

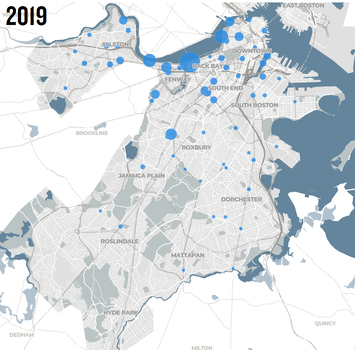

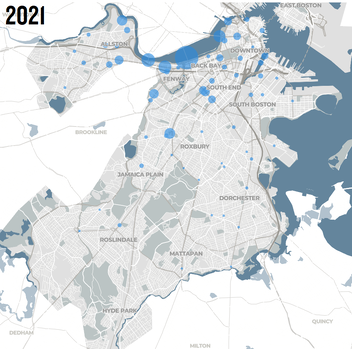

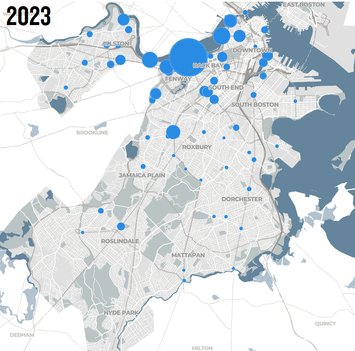

Despite having a hard-core of bicyclists riding on the streets of Boston since the 1970s, the City did not begin installing bicycle infrastructure until 2008. Under then-mayor Thomas Menino, the City hired a Bicycle Programs Manager and began to lay out the steps to make Boston into a ‘world class biking city’. Beginning with a humble but critical painted lane on Comm Ave near Boston University, today the City has more than 70 miles of bike infrastructure, including separated cycletracks, shared use paths, painted lanes, and more in the planning and construction pipelines. Since 2016, the City of Boston has conducted bicycle counts at dozens of key intersections during all four seasons and the trendline is decidedly positive, especially in areas where new bicycle facilities have been installed.

Average Number of Bike Trips Per Day at City Counting Sites 2016—2023

Explore the data yourself at the City of Boston's Bike Counts Database.

In 2011, the City of Boston launched Hubway, a station-based network of more than 600 shared, public bicycles which spread to Brookline, Cambridge, and Somerville in 2012. Blue Cross Blue Shield signed on as the new title sponsor in 2018 and the rebranded “Bluebikes” have expanded the number of stations, bikes, and trips taken every year, providing nearly 25 million rides total by the end of 2024. In early 2024, e-bikes were introduced into the system and have had an outsized impact on ridership. With the City of Boston planning to add 100 more stations in the next year, we can only expect that Bluebikes will continue to provide more connections to neighborhoods, essential destinations, and key transportation hubs.

However, the Bluebikes bikeshare network is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to biking in Boston. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, e-bikes have played an outsized role to make bicycling more accessible and more practical for everyday mobility needs. Furthermore, Greater Boston stands out among U.S. metropolitan areas for its forward-thinking transportation community and expansive network of regional bike infrastructure. Continue reading “Biking in Boston” to dive deeper into urban bicycling and its role in adding flexibility to our mobility network.

E-Bikes to The Future

What is an E-Bike?

E-bikes are bicycles equipped with small, silent electric motors of 750 watts or fewer which provide power assistance when pedaling or accelerating. E-bikes come in a variety of models, with many bikes looking almost identical to their analog, or 'classic', counterparts. In Massachusetts, there are officially two classes of E-bikes defined in an amendment to the General Laws of the Commonwealth.

Class 1 e-bikes have “a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling, and that ceases to provide assistance when the e-bike reaches 20 mph, with an electric motor of 750 watts or less.” (From the MassBike E-Bike Laws Page)

Class 2 e-bikes have “a throttle-actuated motor that ceases to provide assistance when the e-bike reaches 20 mph, with an electric motor of 750 watts or less.” (From the MassBike E-Bike Laws Page)

As of July 2024, Massachusetts law does not have any formal language defining or permitting the use of “class 3 e-bikes," though there is a definition of them in Federal law. According to the Bureau of Land Management, class 3 e-bikes have “a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling, and that ceases to provide assistance when the bicycle reaches the speed of 28 mph” (blm.gov).

Where to Ride

According to MassBike, you can ride an e-bike on most surfaces allowed for analog bicycles, though any prohibition of e-bikes will come from local jurisdictions which oversee the usage and maintenance of public paths. E-bikes can be generally ridden on roadways, dedicated bike lanes, and shared-use paths unless otherwise prohibited by a local jurisdiction. In the case of natural surface trails, some are designated as foot trails, others are designated as mountain bike trails, and yet others allow both pedestrian and bike access. In any case, e-bikes are generally prohibited from these natural surfaces unless specifically allowed by the local jurisdiction. As such, it’s important to be aware of who maintains your local parks and public pathways, and to find out the rules before riding.

MassBike’s Massachusetts E-Bike Resource page has a great, printable flyer that includes a reminder of e-bike classifications and where you can ride.

Interested in e-bikes and want to learn more? Check out the video below on things to consider before riding an e-bike. Special thanks to New Horizon Bikes and sponsored by PeopleForBikes and the League of American Bicyclists.

E-Bike Product Safety

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) mandates that all e-Bike manufacturers and distributors must ensure that their products are evaluated, tested, and certified before being sold. There are a variety of regulatory requirements for the different components on an e-bike, but the UL Solutions (UL-2849) certification is the main regulatory evaluation for e-bike electrical systems and batteries, as recommended by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI).

With the increase in e-bike usage across the US, there is also growing concern regarding the safety of riding, storing, and charging e-bikes. The UL 2849 certification ensures that all properly evaluated and certified e-bikes are safe for riding, storing indoors, and charging with a compatible outlet. It gives proper “electrical and fire safety certification by examining e-bikes’ electrical drive train system, battery system, and charger system combinations” (UL Solutions).

While e-bikes are thoroughly regulated for safety in the United States, it is still important for everyday riders to be aware of the specifications of their bike equipment, and to ensure that their bikes are set-up as intended by the manufacturer. When acquiring an e-bike from an unofficial source (not coming from a manufacturer or respected retailer), riders should look to their local bike shops for assistance in verifying the safety of their bikes. Using a different bike/battery combination from the one specified by the manufacturer, modifying a bike’s electrical system, modifying a battery, or operating any combination of modified e-bike components all pose safety concerns when it comes to riding, storing, and charging e-bike equipment.

As with any mechanical electrical equipment, it is important to handle your e-bike and battery with care by always adhering to the instructions accompanying your product. For an introductory summary of best practices to handle your e-bike and battery, check out this free-to-watch video produced by New Horizon Bikes and sponsored by PeopleForBikes and the League of American Cyclists.

An Attractive Ride

Electric bicycles are increasingly popular in the United States for everyday transportation. In 2018, according to the National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC), e-bikes were in the “early adoption” phase in the US market, with roughly 325,000 sales recorded nationwide in that year (read study here). By 2022, annual e-bike sales in the US hit 1.1 million (energy.gov) and demand continues to grow in 2024. In early July, Minnesota launched its first-ever e-bike rebate program and in the first 18 minutes, the state received 14,000 submissions for 1,300 vouchers (Lakes Area Radio).

The rise in e-bike popularity is fueled in part by the introduction of e-bikes through public bikeshare systems. Here in Boston, the Bluebikes network began adding e-bikes to the system in January 2024, deploying a total of 750 over a few months. While e-bikes comprised just ~15% of total bikes available, they were ridden for 26% of all trips between January and June – 505,000 rides out of nearly two million. The roughly 2.5x preference is consistent with data from other markets.

With their added power and ease of use, e-bikes have surged in popularity among experienced bicyclists and first time riders because they help remove barriers of entry to bicycling: hilly terrain, lengthy distances, and physical exertion (NITC e-bike ridership study). Older people and those living with disabilities or medical conditions may also have difficulty riding an analog bike. By making riding easy, enjoyable, and less strenuous, e-bikes make active mobility more accessible for many.

Why Don't We See More of These?

Despite the trends detailed above, bicycles in the US are still seen by most as recreational and not an option for daily transportation. Americans typically fall into four well-documented “bicyclist” archetypes, originally defined by Roger Geller in his 2009 paper, “The Four Types of Cyclists,” published by the Portland Office of Transportation. The four kinds of cyclists are:

“The Strong and Fearless”

“The Enthused and Confident”

“The Interested but Concerned,” and the

“No Way No How”

Initially based on Portland’s commuter population, Geller estimated that around 7% of Portlanders were “strong and fearless” or “enthused and confident” about bicycling for regular transportation. Roughly 33% would never consider picking up a bike, the “no way, no how” cohort. Geller estimated that the largest group of Portlanders—the remaining 60%—were “interested but concerned” about bicycling, meaning that they currently enjoy or even remember enjoying riding a bike as a kid. The reason they don’t ride more often is fear, not of bicycles themselves, but of sharing roads with automobiles. Geller estimated the “interested but concerned” would ride a bicycle more often if “they felt safer on the roadways” and if there was safe, separated infrastructure for bicyclists.

Geller initially created these four categories of cyclists based on his own anecdotal experience As the Bicycle Coordinator for the City of Portland. His model was later endorsed at the 2006 Pro Walk Pro-Bike Conference in Madison, Wisconsin by 20 transportation professionals with a combined 150+ years of experience. Since then, studies such as those conducted by Jennifer Dill and Nathan McNeil (INSERT LINKS), have supported his anecdotal conclusions with surveys documenting people's perceptions of the safety of riding a bike around cars. Since the mid-Twentieth Century, the federal government, state and local authorities have prioritized the movement of people in personal cars above all else so the apprehension Geller and others have identified makes sense. But things are changing, and many US cities are accelerating the design and implementation of the trails, cycle tracks, and bike lanes that help people feel safe and more willing to consider a bike for short trips.

How Does Greater Boston Stack Up?

After nearly two decades of local communities ramping up the installation of safe, cycling facilities, Greater Boston is on the verge of connecting the regional trail system with local infrastructure into a comprehensive network. Our compact geography, high population density, and complementary public transit system together will enable sustainable mobility at an unprecedented scale. According to the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, 57% of all trips in Massachusetts are three miles or fewer and most of those are taken in cars (Bicycle and Pedestrian Update 2021). Furthermore, A Better City analyzed the commutes of more than 59,000 people coming into Boston and found that nearly 40% of them live five miles or fewer from where they work with ~25% more living within ten miles. These are viable distances for bikes and e-bikes, whether making a connection to the T or riding all the way on the growing bicycle network.

Boston’s roadway congestion ranked fourth worst among US cities and eighth worst in the world by the 2022 INRIX Traffic Scorecard. The transportation sector accounts for 36% of GHGs in Massachusetts, which makes it the largest single-source contribution of any sector (Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Metrics | Mass.gov). Bicycles can help to reduce both roadway congestion and related GHG emissions by providing an alternative to driving, especially for short-distance trips.

Bike Infrastructure in Greater Boston

MAPC Landline Network Plan

The Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) leads a regional effort to create a network of shared-use paved paths, protected bike lanes, and foot trails connecting the communities of the Greater Boston Area. The Landline Network Plan is an initiative in coordination with the LandLine Coalition to create an inventory of all the paths, bike lanes, and trails in the region. MAPC has two active mapping resources documenting the existing, currently under construction, and envisioned paths in the LandLine Network: The LandLine Greenway Network Map focuses on main travel routes while TrailMap is a more comprehensive collection of regional walking and cycling trails.

Types of Bike Infrastructure

As far as bicycles are concerned, there are three types of surfaces that can be found in Greater Boston’s growing infrastructure network: Shared-use paths, cycle tracks, and bike lanes. Furthermore, cycle tracks break down into two categories with different levels of bicyclist protection.

Shared-Use Paths

Shared-use paths are wide, paved surfaces that serve both pedestrians and bicyclists. Typically, these types of surfaces are part of public parks and undeveloped land and are always completely separated from automobile traffic. The Greater Boston Bike Lines (further into this section) are examples of shared-use paths.

Cycletracks

Cycle tracks are paved lanes dedicated to bicycles, and it is unlawful for pedestrians or motorists to obstruct these lanes. They are commonly found in urban areas running parallel to roadways, though a key characteristic of cycle tracks is that they are always separated from automobile roadways so that cars cannot cross into the lanes. There are, however, two different methods of providing protection to bicyclists in cycle tracks. The first method is the implementation of built infrastructure such as curbs, garden beds, sidewalks, or other kinds of barriers that physically inhibit entry by automobiles, as shown in the picture above. The second method is the deployment of bollards and bright-colored paint to prohibit automobile entry using physical and visual cues, though these features are less effective at preventing automobile entry. See below for an example of a cycle track designed with bollards and paint.

Bike Lanes

Bike lanes are the most rudimentary form of bike infrastructure in the sense that parts of automobile roadways are allocated specifically for bicycle use. The creation of bike lanes involves using paint to designate the separation between motor traffic and bicycle traffic. They are different from cycle tracks in that they are physically part of the automobile road surface, while cycle tracks are physically separate.

Greater Boston Bike Lines

The Greater Boston Bike Lines are the major shared-use paths connecting Greater Boston with the City's downtown neighborhoods and are part of the MAPC Landline Network Plan. Below are highlighted the five established Landline routes that take bicyclists from different parts of Greater Boston to Downtown.

There are five arterial routes: the Charles River Path, the Minuteman Bikeway via the Somerville Community Path, the Northern Strand, the Neponset River Trail via the Boston Harbor Walk, and the Southwest Corridor. These routes are comprised of many park segments and connected trails as they cross through adjacent municipalities. Together, the Bike Lines provide accessible, protected, and fast active mobility options for commuters and residents looking for flexibility moving around Greater Boston.

Greater Boston Bike Lines Map (Above): Scroll within the map frame or click the "+" and "-" icons in the lower left-hand corner to zoom in and out on the map. Click the small screen icon in the top left-hand corner of the black bar at the top of the frame to see the maps' layers. From here you can toggle on and off each of the five major arterial routes in addition to bike lanes and protected bike lanes from the MAPC's Trailmap resource.

Charles River Path

The Charles River Path begins as the Charles River Greenway in Waltham between the Brandeis/Roberts and Waltham Commuter Rail Stations on the Fitchburg Line. It follows the Charles River through Watertown and Newton, before turning into the Dr. Paul Dudley White Bike Path which continues along the Charles River Esplanade through Brighton, Allston, Fenway-Kenmore, and Back Bay. The Charles River Path concludes in the West End at the Charles/MGH Red Line Station.

MINUTEMAN BIKEWAY VIA SOMERVILLE COMMUNITY PATH

Beginning in Bedford Center, The Minuteman Bikeway runs through Lexington along a former railroad right-of-way, and roughly follows Mass. Ave and Mill Brook through Arlington. The Bikeway formally ends at the Alewife Brook Reservation and the Alewife MBTA station, but the route continues along Alewife Linear Park until intersecting with Mass. Ave at Cedar Street in Cambridge. In Somerville, the route becomes the Somerville Community Path where it runs through Davis Square before connecting with the Medford/Tufts extension of the Green Line at Magoun Square. Finally, the Somerville Community Path parallels the Green Line until linking up with the Charles River Bike Path at Science Park and the head of the Charles River.

NEPONSET RIVER TRAIL VIA BOSTON HARBOR WALK

The Neponset River Trail begins at the Mattapan MBTA station servicing the red line trolley extension at Blue Hill Ave in Mattapan Square. It runs along the Neponset River on the Mattapan-Milton line all the way to the Neponset Ave Bridge on Route 3A in Quincy. It then runs through Joseph Finnegan Park and formally terminates at Tenean Beach in Dorchester. Currently under construction is a connector between Tenean Beach and Dorchester Shores Reservation which will link the Neponset River Trail to the Boston Harbor Walk. Once established, the Neponset River Trail will encircle UMass Boston via the Boston Harbor Walk, pass by Moakley Park, and wrap around Old Harbor prior to terminating at Castle Island in South Boston.

NORTHERN STRAND

The Northern Strand, also known as the Bike to the Sea Trail, currently begins at the end of the Community Path of Lynn but will soon extend all the way to Nahant. The path runs along the former right-of-way of the Boston & Maine Railroad in Saugus, Revere, Malden, and Everett, and terminates at the Encore Boston Ferry Dock across the Mystic River from the Orange Line in Assembly Square in Somerville.

SOUTHWEST CORRIDOR

The Southwest Corridor Park was initially a former railroad right-of-way selected as the site for a major highway development which would bring I-95 directly through Boston's Downtown. With the help of opposition from the local community and leaders in the Massachusetts State Government, the highway project was never completed. Today the Southwest Corridor is a public greenway beginning at the Forest Hills Orange Line station, running parallel to the Orange Line and Northeast Corridor through Jamaica Plain and Roxbury before terminating at the Back Bay Orange Line Station at the Prudential Center.